Not Well, but Home…

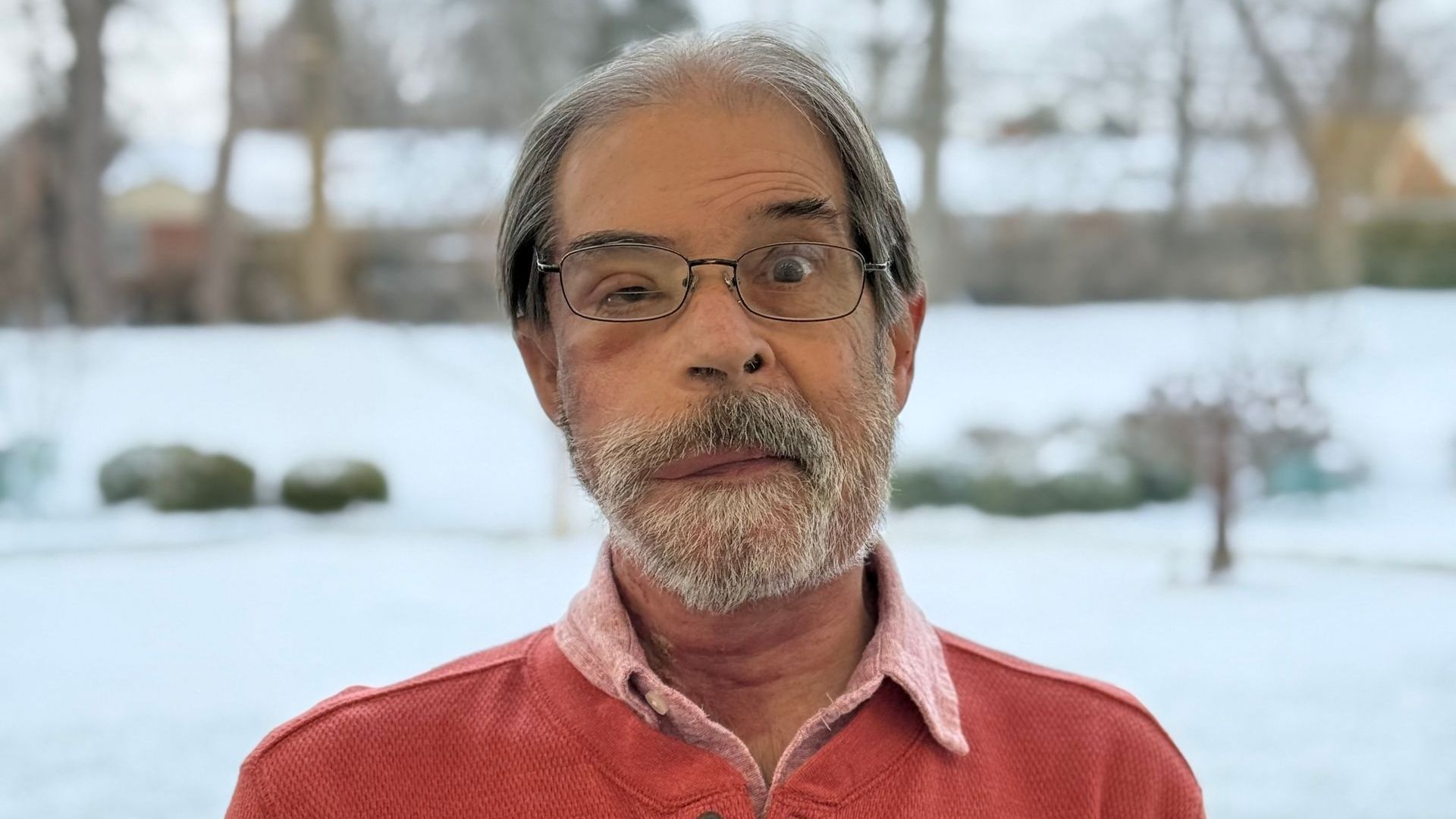

This article was originally published in "The Courier Journal Magazine," August 6, 1978, and written by Sylvia Wrobel.

…A woman in Lexington has been the first patient in Kentucky to use Hospice, a program that helps when a person’s days are numbered.

The cards that 8-year-old Ann drew for her hospitalized grandmother read “Get well soon.” And then one day they simply read, “I’m glad you are coming home soon.”

Not well. But home.

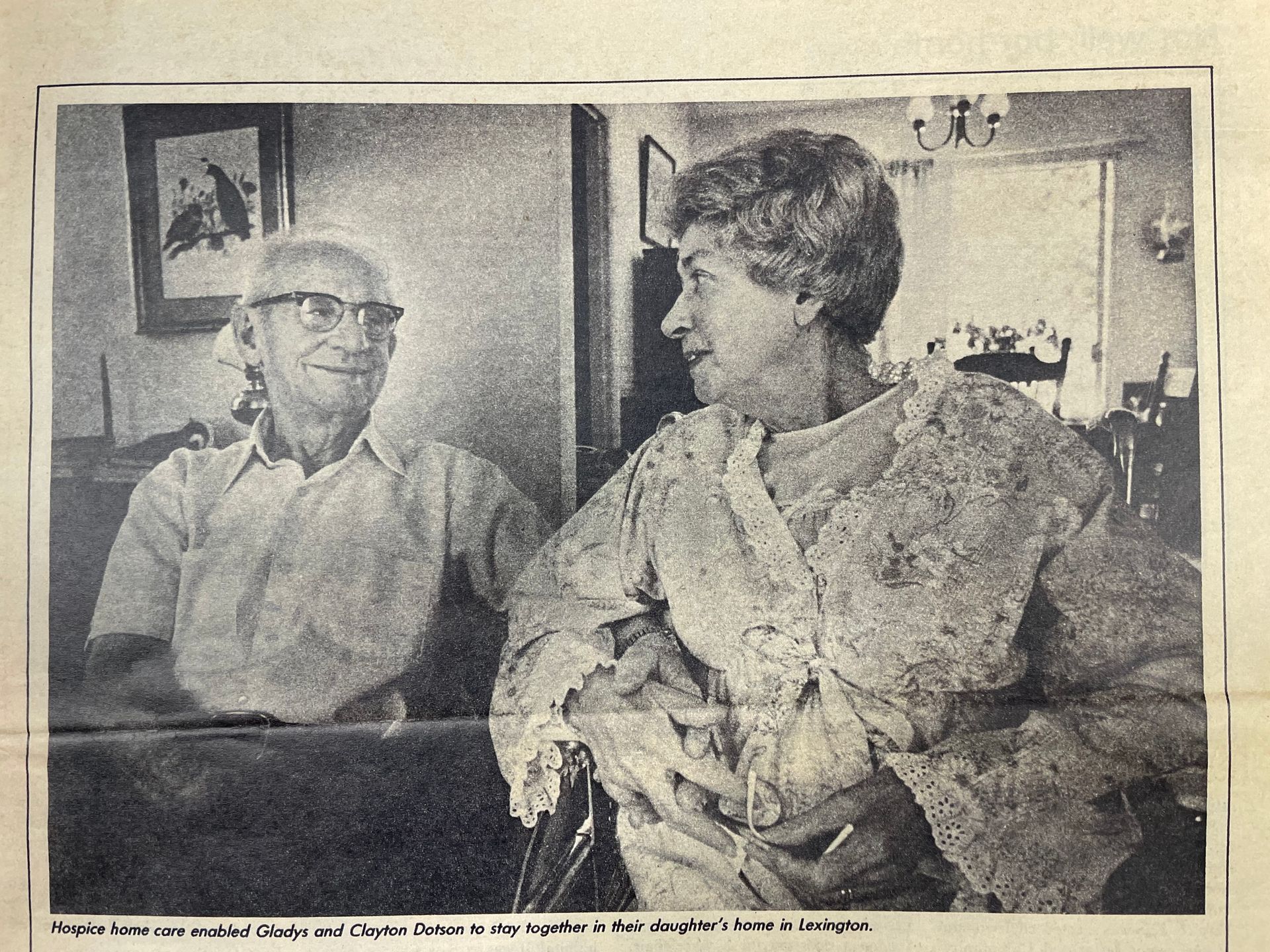

Because of the Ephraim McDowell Community Cancer Network program called Community Hospice, Ann’s grandmother, Mrs. Gladys Dotson, was given the chance to leave the hospital where she had been receiving chemotherapy and constant medical attention and go home to live as long as possible.

So did all our grandmothers face their deaths a century ago. If they lacked the benefits of present-day drugs, radiation therapy, surgery, and other knowledge that has improved the prognosis for the large group of diseases called cancer, they nonetheless had the strong emotional and practical support of large families and communities.

Mrs. Dotson, as the first patient accepted into the Community Hospice, has had it all.

In medieval Europe, hundreds of hospices opened their doors to the hungry wayfarer, the woman in labor, the weary traveler – or the traveler at the end of the most hazardous journey, life itself. Unlike today’s hospitals, which are rightly intent on curing, the hospice offered protection, refreshment, fellowship and cherishing, even in the face of death.

This old idea reappeared in England in the late 1960s, chiefly at the hands of Dr. Cicely Saunders, who founded St. Christopher Hospice for the Dying. Hospice itself was a realization that the terminally ill patient had not had enough attention and help, says Dr. David Goldenberg, executive director of Ephraim McDowell. (The non-profit corporation received a $320,343 federal grant in mid-July to assist in the establishment of a cancer research center at the University of Kentucky.)

Crossing the ocean, the hospice movement grew rapidly, with more than 100 American programs firmly established – among them the Lexington program and another in Louisville. They allow a patient – like Mrs. Dotson – to go home to receive health care and counseling by a team of health professionals and other volunteers.

The first patient in Kentucky to enter a hospice program was born in Whitley County in 1905 and moved to Hazard in 1919. Her father was the undertaker there.

Clayton Dotson, a traveling salesman of tailor-made clothes, married this pretty local girl. In 1936 he bought Goad’s Hardware Co. in Hazard but continued to travel. He never bothered to put his own name on the sign. Gladys kept the books and helped out in the store when he was on the road.

They had two daughters, Doris and Lois. They kept a garden, went to the Baptist church whenever it held service or social. Their best friends were often family as well.

The girls grew up. Lois moved to Illinois, became a reporter, had two children. Doris, a schoolteacher, had a child.

Dotson retired, first from traveling, then from the store. He and his wife sat on the porch shelling peas and talking the evenings away.

“They never had a single argument I can recall,” says a daughter.

“Well, I never once saw anything about Mother I didn’t like,” says Dotson.

In short, they have led a calm and happy life, the kind perhaps no longer easy to have. Dotson was about 10 years older than his wife, and because his diabetes was becoming more difficult, the couple thought she would outlive him. After all, Gladys was the healthier as well as the younger; the woman – tougher – according to the actuarial table.

But in 1972 Mrs. Dotson had a threatening lump in her breast treated by mastectomy removal.

In November last year, she fell ill again and in December fractured a shoulder that was weakened because cancer had spread into her bones. Hormone treatment failed: chemotherapy was begun.

In February this year, she telephoned to cancel an appointment with Dr. John Cronin, a Lexington, oncologist, a specialist in cancer. She had found she couldn’t use her feet. Ger her here immediately, he ordered, and she went into surgery that night to relieve the spinal compression caused by the growing cancer.

Surgery, together with a brace, restored her to her feet. But at that time, it was obvious to Cronin and his colleagues that the cancer was in her bones and progressing despite chemotherapy. It had also moved to her skin. Mrs. Dotson was nearing the end of her life.

About the same time last November that Mrs. Dotson had her first relapse, a group of physicians, nurses, educators, ministers and others met at the Ephraim McDowell Community Cancer Network Offices in Lexington to discuss the possibility of providing hospice care to terminally ill patients. The prime mover and organizer of this meeting was Dr. Ann Blues, assistant director for cancer education at McDowell. Her concern for the care of cancer patients in central and eastern Kentucky had taken focus. This was the result of visits and correspondence with Dr. Saunders, the director of London’s St. Christopher Hospice, and as the result of the number of requests on the statewide Cancer Hopeline telephone – what can I do with and for my dying husband, wife, parent, child to make it easier?

What emerged during this first meeting, and those that followed, was a group of persons who had been interested in hospice, and in some cases providing bits and pieces of it. Among them:

- A surgeon who said at the first meeting, “I practically run a hospice now. I let the whole family around the hospital bed, sleep there, eat there. I come in and do what I can, what at some point or other becomes just a needle to stop the pain. It has to be made easier on all of them.”

- Doctors like Cronin, making their Saturday and Sunday home visits.

- Nurses at the local Health Department, already providing care in the home.

- Priests, rabbis, ministers, counselors of all kinds, including a successful financial consultant who has worn a beeper on his belt for the past two years. This enabled him to abandon briefcase and tickertape at an instant’s notice to be at the bedside of the terminally ill patients with whom he works at various hospitals, or with their relatives in the hard weeks following a patient’s death.

- Episcopal nuns who ran St. Agnes House, where mostly Eastern Kentucky residents can live inexpensively and in community while in Lexington to undergo radiation therapy for cancer.

And there were others, such as Mrs. Binnie Bailey, the cheerful and energetic patient representative here at St. Joseph Hospital in Lexington. Mrs. Bailey’s work with hospital patients and family members, sometimes located throughout the world, had made her an advocate of family-oriented health care, including hospice. She was elected chairwoman of the newly designated Community Hospice of Ephraim McDowell Community Cancer Network, Inc.

The McDowell program provides clerical help, educational workshops for physicians and volunteers, and the vital training for a family involved in hospice. It was not financially feasible to build a hospice like St. Christopher or even to outfit a special hospital wing. But the philosophy that grew out of Dr. Blues’ meetings was the need for a home care program. The terminally ill cancer patient for whom this first hospice was being designed would not enter yet another institution. Instead, the hospice would go home with the patient.

In the next few months, committees dealt with problems of home care and services for the terminally ill. And each meeting drew in a larger number of volunteers: physicians, nurses, clergy, other counselors, dieticians, dentists, psychologists, volunteers concerned with ways to modify the home (widen a doorway for a wheelchair, alter the bathtub or toilet, rearrange furniture for easier movement). A laundry committee of one was formed by a hospital worker experienced with dealing with the drainage caused by some kinds of cancer and the stains and smells that result.

McDowell, true to his promise to provide research and technical expertise, along with Mrs. Bailey, began compiling what has become one of the largest collections of materials on hospice and home care for the cancer patient. (This is available free to hospice members, at photo-copying costs to others.)

Last March, the Lexington organization was ready to take on a patient, ready to help someone, and equally ready to learn how better to do its job.

“When they told me,” says Mrs. Dotson – no once asks what, but that is a politeness on the part of the listeners rather than shyness on the part of the Dotsons – “We didn’t know what to do. We didn’t want to stay in the hospital. It was hard on Clayton, there all the time. Hard on us all. We didn’t know what we should do.”

Dr. Cronin suggested hospice.

By then, the physicians’ committee, headed by Dr. Phillip DeSimone, an oncologist and chief of hematology at the Veterans Administration Hospital, had established four criteria for admission.

First, the patient should have only weeks to live, and know that and accept it.

Second, the patient must bring his or her own physician to the program, a physician willing to endorse hospice concepts. These include emphasis on symptom control, willingness to work within the medical direction of the program and with volunteers and other professionals on the committee and to be available to the patient and family when needed. This was easy for Cronin, who was already available, and who, as chairman of the hospice home care committee, had helped set up those concepts.

Third, and more difficult, was the requirement that Community Hospice patients live within the geographic limits of the Lexington-Fayette County Health Department with which it is also affiliated. The Dotsons were from Hazard, where a similar hospice group was forming, also under the auspices of McDowell, but was not yet ready for patient care. (The Hazard group presently is preparing to admit a patient.) This problem was solved by the quick offer of the Dotsons’ daughter Doris Curtis and her daughter Ann. The house at Hazard could be closed up, at least for a while, and home would be in Doris’s brick house on a pleasant tree-shaded street off Versailles Road in Lexington.

Fourth, even more difficult, but the true heart of the home-care hospice program – the patient must have his or her own primary-care provider. This will most often be a spouse or other family member, trained by members of the hospice team.

Who could do this for Mrs. Dotson? She would be moving away from her neighbors and brothers and sisters in Hazard. Daughter Lois could not leave husband, job, and small children in Illinois. Daughter Doris left home early each morning to work. Not only was she gone all day, but she also came back to the responsibility of a young daughter and as drained as only an English teacher in a room full of junior-high students can be.

“But I’ll be home all day,” said Mrs. Dotson’s husband. He never doubted he could manage it.

Others in the family did. Not that he didn’t love his wife dearly, but he was born in the previous century, after all. He had diabetes, was hard of hearing. He was unaccustomed to housework. He had been a pampered husband; he was the first to admit. His daughter Doris was particularly dubious. “I remember when Mother felt bad, Daddy swept the rug, but…”

“No, I wasn’t any expert on cooking or washing dishes,” Dotson says cheerfully. But he was right. He could do it, as well as the physical care and attention his wife needed.

When Mrs. Dotson was accepted as the first hospice patient and moved home, hospice volunteers came out to work with Dotson. They helped with meal planning and cooking, because Dotson would have to prepare breakfast and lunch during the week. They helped lift his wife from bed to wheelchair and back again. They helped bathe her, administer medication, and teach Dotson how to know when he needed to call someone on the hospice team for help.

Someone was at the door often: Cronin and a physical therapist and a nutritionist. A nurse appeared almost immediately: Shelley Boatwright, a perky young woman who looked barely old enough to be the babysitter, but whose self-confidence and expertise immediately put the Dotson’s minds to rest. The nurses are wonderful, they all agree. They do “the hard part,” making the rest possible.

Boatwright, a home-care program nurse, is the Lexington-Fayette County Health Department’s contribution to the hospice. She goes to the Dotson’s at least once a week, sometimes three.

Eventually, through grants and donations, the Community Hospice hopes to hire its own registered nurse to organize and direct the home-care team.

Apart from regular visits, nursing care is never more than a telephone call away. It’s available through the Cancer Hopeline (1-800-432-9321) a toll-free telephone number that anyone in Kentucky can call with questions and pleas for help. Hospice also has a line at McDowell. And local nurses volunteer their time – from a few hours to an entire day – to go if a call comes that they are needed. In Mrs. Dotson’s case, no one has ever gone, although the Dotsons did call the number once after hours for advice on a broken partial dental plate.

The telephone service embodies one of the most important ideas in hospice care: You are never alone. Hospice will teach you to manage. But if the moment comes when you can’t, someone will be there who can. Plans are also being made for back-up beds in the Veterans Administration or other hospitals.

Dying is a personal experience, but waiting for death within the framework of the McDowell hospice program has been, for Gladys Dotson and her husband and daughter and grandchild, a little like being adopted by an entire family. The health professionals and hospital administrators, like Mrs. Bailey stopped by to give advice and get it – and then went by again as friends. In addition, there have been at least two non-health professionals in frequent attendance.

Joan Crowe, a graduate student in counseling and a volunteer on the Cancer Hopeline, was trained as a hospice worker. It was she who gently led Dotson into the mysteries of the kitchen and housekeeping in general, took him to the grocery store when Doris was in school, spelled him for walks around the neighborhood, popped in with lettuce and strawberries, even sprayed the apple tree in the backyard. When the Dotsons’ daughter Lois came for a long visit, Joan brought a tape recorder and encouraged Mrs. Dotson to speak of the children’s growing up in Hazard.

And Jay Pierce, the head of the clergy committee of hospice, had been seeing Mrs. Dotson since she entered the hospital. When she went home, he built the ramps on the front and back steps with his own hands. Three times a week he says morning prayers, brings books, discusses the garden, religion, dying, death not as a punishment or a failure, but as a part of the cycle obvious in the garden outside the window.

The Dotsons could have requested a Baptist (or any other) minister or counselor, but they had met Pierce already. And he and they amalgamate Baptist and Episcopal prayers and tenets. He prays for a cure, but the emphasis in hospice, as in his visits, is not on the cure, but on living out the gift of days.

And a death like this is a gift, too, says Pierce. It gives a person a chance to look back over a lifetime and see it in perspective, to make judgements about the satisfaction they have had, what they have done and known. In many ways, it helps to have a stranger with you, someone you can tell it to.

In many ways, too, this seems also to have made this close family closer, he says. Mrs. Dotson’s grandmother Ann has learned about life, what few children her age do. She has seen her grandparents and mother coping with an extremely difficult time, and coping well. And she knows death to be an ending – she says often she worries because “Nanaw” and “Dada” can’t do all the things they used to, like back in Hazard, and she knows that death is a time for an outpouring of love and support.

Since Mrs. Dotson’s entry into the program, the telephones in Ephraim McDowell and in Mrs. Bailey’s St. Joseph office have been ringing with people who want to bring their wives or husbands, parents or children home. McDowell is setting up training programs in various towns and is trying to help other communities form their own volunteer groups as a regional Cancer Network. Patients are being accepted in Danville, Hazard and Lexington.

In Louisville, a volunteer group entirely apart from the McDowell network, although cooperating with it, opened an office in June and has begun visiting patients dying from any cause, not just cancer. Headed by A. Robert Crawford, director, and Patricia Webb, R.N., head of volunteers, The Hospice, Inc., sees patients at home, in the hospital or elsewhere. There is no charge for the work of the Hospice itself. The Hospice, Inc., number in Louisville is 1-502-584-4834.

Through hospice, explains Dr. David Goldenberg, executive director at McDowell, communities have been told something they can do to combat cancer, which claims about 6,000 Kentucky lives each year and accounts for almost a fifth of all deaths in the state. He thinks that hospice can lead to increased community involvement elsewhere, just as it has in Lexington.

Our Lexington physician and specialist in community medicine, Dr. Mac Vandiviere, has given much time and effort to coordinating hospice programs across the state. Patients who go to Lexington or other medical centers thus would be able to return to their own communities in a local hospice program. At present, Vandiviere himself provides such referral help and has been known to spend as much as eight hours straight with a patient who called the Cancer Hopeline.

Goldenberg, a research pathologist nationally noted for his work in radio-active tracing tumors, was heavily involved in creating a Kentucky Cancer Commission. He says he has two goals. The first is to make Kentucky, through McDowell, UK, and the University of Louisville, as capable of managing cancer as any place in the world. For 99 percent of all cancers, this is already true, he says.

The second is to see that research finds ways to reduce the death rate from that vast collection of diseases called cancer, until eventually no one dies from it at all. If he’s successful, hospice for cancer patients will no longer be needed.

But now, at the end of July…

Mrs. Dotson rests a lot. As the workers at St. Christopher tell their patients, it’s hard, tiring work, dying. She had hoped to go with her brother in his trailer to visit her daughter Lois in Illinois, but it takes increasingly more energy simply to go to meals at the table. In the afternoons she sits on the patio and watches Clayton garden or plays with Ann. People visit. Cards arrive daily in the mail.

Gladys Dotson recalls her 73rd birthday in May. The house was filled with family, people from Hazard, new neighbors in Lexington and many members of the Hospice team. It was a happy celebration.

“Yes, the days pass on right well,” she says.

“In fact,” says her doctor, “she’s done far better than we ever expected. We thought her condition would continue to deteriorate at the same rate in the hospital, and it hasn’t.”

Why?

“Maybe the hormone therapy is working better than we thought. Maybe it’s part of the impossibility of predicting life span.”

Mrs. Dotson views it more simply. “I knew I felt better the minute I got home.” She has nothing but good to say of hospice. “Everybody has been wonderful. We’re so grateful for this program. It’s made it possible for me to remain near the people I love. It’s made everything easier for me and for Clayton. It was hard on him in the hospital.”

(Expensive, too, incidentally. Some of the expenses of hospice are paid by Medicaid and other third-party payers, while other bills are covered by the volunteers themselves and donations. But the hospice services are free to patients, many of whom are expected to have nothing left after the heavy costs of the illness that takes them to the hospice.)

Doris Curtis in particular feels her mother has done well in part because of an intensely strong religious faith, in part because she dreads leaving her husband alone, and because she has been at peace at home.

“Yes, attitude is important,” Dr. Cronin says. “I don’t know what all has gone into her remarkable lasting power. Her hospice experience has been a great success.”

The success of the hospice movement is not the cure, of course, but in the triumph over pain and fear and loneliness.

Dr. Cicely Saunders, who began in London the movement that Mrs. Gladys Dotson and her family have made a reality in Kentucky, tells her patients: “You matter because you are you. You matter to the last, and we will do all we can not only to help you die peacefully, but also to live until you die.”

And that is what Mrs. Gladys Dotson has done. The hospice program – and many people who have forgotten what our grandmothers knew – are grateful to her for showing that it can be done.